Sitting the gallery as I have just found out today, is a very good way to work on my Japanese. Not a lot of people in Japan speak English, so I’ve become very good at gestures and using the few words I do know. When I knew I was coming to Japan, I signed up for a beginners course at the Canadian Japanese Cultural Centre in Montreal. I was away for an exhibition in Bogota and missed one lesson near the beginning unfortunately and then another because of illness, so I never really felt like I was able to keep up. The words just seemed so strange to me, I could not get them to stick in my head. Very important words, like sumimasen, (Sorry) just would not sit straight; its parts would move around and I would find myself saying samisen or siumasen. Or, the phrase you need to memorize when meeting someone for the first time, Hajimemashite, Karen desu, yorishiku onegaishimasu. YIKES! all that just for hello, I’m Karen -nice to meet you. I still continue to confuse the sounds of the vowels – they are exactly the same as the vowel sounds in French – the i becomes an ee sound and the a is short like ah and e is aye, same as é in French.

Shortly after arriving in Tokyo, I looked around to find a language school where I could continue to learn. I soon realized that I had arrived just a bit too late to sign up for any group classes – they had already begun or where full. So private lessons in a private institute was my only option. I liked it; I had a good teacher and to start I had three lessons a week. I thought I was doing really well and began to imagine the day when I could communicate and understand. That was before my teacher showed me how to count objects. If you are ordering two coffees at a restaurant, that would not be ko-hi ni kudasai (thanks) it is ko-hi, futatsu, kudasai! Then I asked her, are there more systems than just these? She shook her head as if to say, ah yes, I know we are completely crazy and then it truly dawned on me that ichi, ni, san was for money and time only. There are more ways to count in Japanese than just one, two, three, and in fact there are whole dictionaries for counting systems only: the days of the month are all numbered in a system, long skinny objects : hons, flat objects, people, small animals, books, cars, even a system for counting the scales on fish I have been told. For days afterwards, I was completely deflated thinking…I’ll never be able to speak this language. But then, I realized that it didn’t matter too much for now, they understand when I use the ichi, ni, san system for everything.

Japanese is a dense and layered language. Someone mentioned that often when learning another language we are able to understand more than we are able to communicate, but that is not the case with Japanese. You may be able to communicate something, but understanding the response is much harder. I don’t know enough of the language yet to be able to confirm this, let alone to offer a reason. I find the cadence or rhythm interesting – something like this… da-da, da-da,DAH..or da-DA. Can the rhythm of language be given a time signature? If so, it feels like Japanese would be a 5/4.

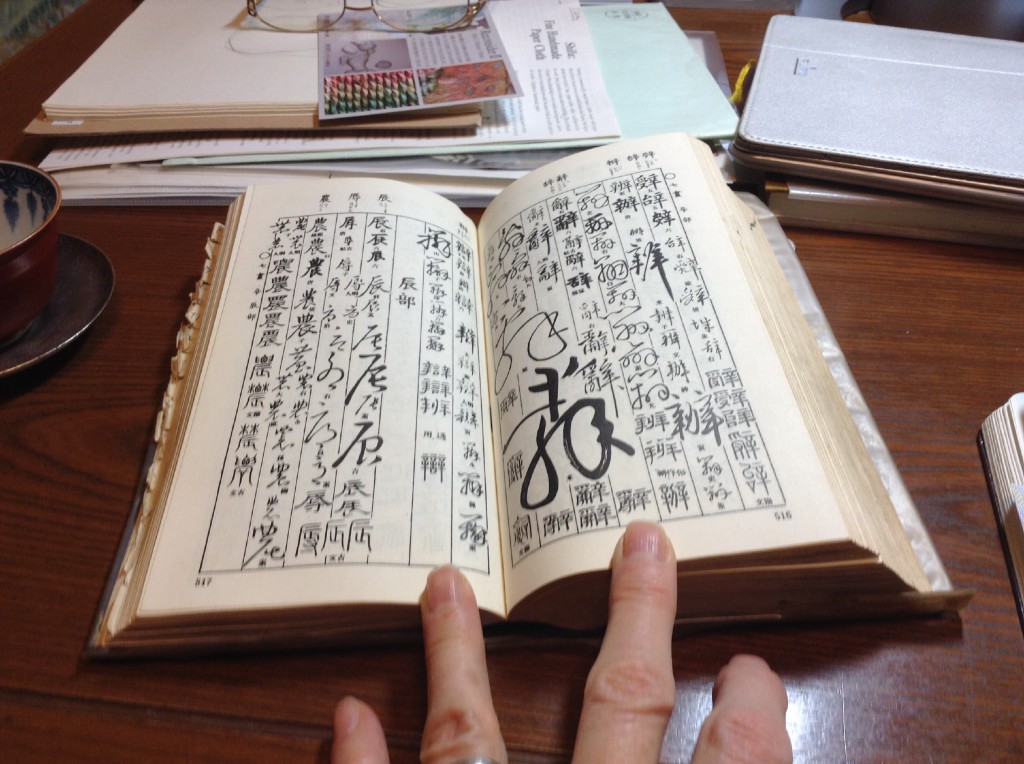

Learning to read and to write will be and is for many Japanese and Chinese a lifelong enterprise. Written Japanese is a combination of three different types of alphabets and scripts: kanji, hirigana and katakana. Children first learn hirigana and katakana which are alphabets and phonetic, meaning they are based on sounds. I can decipher words written in these alphabets slowly, like a grade one child sounding out the letters, but kanji -uh! that is like trying to read a painting and I have no idea where to start. The Japanese adopted kanji from the Chinese as their way of writing some centuries ago, but before they did have a phonetic-based alphabet of their own. Hirigana is the alphabet women developed in order to communicate with each other as they were not allowed to learn kanji. Katakana is the alphabet used to write foreign words that are absorbed into current Japanese usage. It allows for easy absorption of English words and their language is full of Japlish. In katakana and hirigana the letters are complex sounds of a either a single vowel: a,i,u,e,o or a combination of these vowels with consonants like ka, ki, ku, ke, ko, sa, ta, na, etc. It does make for a lot of letters to learn and remember: 46 in each of the alphabets, plus 1000 currently used kanji characters that students must know before graduating and over 5000 possible characters that can be used. That’s some big dictionary.